The Charm of the Highway Strip

by 3amguy

(Published in *Gulf Coast*, 2008)

Everything Jack Kerouac wrote for about a decade was a draft of On the Road – including On the Road. The novel that was published in 1957, ten years after Kerouac made the first of the five cross-country road trips it recounts, was allegedly produced in 1951 in a mythical three-week Benzedrine-fueled round-the-clock writing session, when Jack sat down at a table in his new wife Joan Haverty’s Chelsea loft and hammered out an unpunctuated single-paragraph 120-foot long novel-scroll on a roll of Western Union typing paper. Then, as the story goes, he bundled it in his arms and, still high on speed and caffeine and nicotine, carried it to Harcourt Brace, the publishers of his first and up-to-then only novel, The Town and the City, and unfurled it at the feet of his editor Robert Giroux, announcing that it had been dictated to him by the Holy Ghost and that he wouldn’t change a word.

Well, the story’s mostly false, and that novel doesn’t really exist. For one thing, he punctuated plenty. And it wasn’t a single roll of Western Union typing paper, it was eight sheets of architectural tracing paper that Jack found in the corner of Joan’s place, and which he cut to size and taped together. The paper had belonged to Joan’s dead ex-boyfriend Bill Cannastra, from whom she inherited the loft after Bill climbed halfway out the window of a moving subway car and got beheaded. You see why Jack didn’t need to invent things. He went around marrying dead guys’ girls and getting high with William Burroughs and letting Allen Ginsberg blow him once in a while in 1948 with Bess Truman still sleeping in the White House. And then he wrote about it. He liked drugs and drama, and he liked to type, and by the time he was done typing what he was maybe calling The Beat Generation or maybe Gone on the Road or maybe Flower That Blows in the Night, Joan was through with him and she arranged to be found in their marriage bed with a waiter.

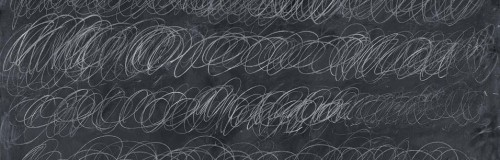

Jack split to his buddy Lucien Carr’s place, where Ginsberg was also living, and that’s where he finished the book, and where the last few feet of the original scroll were eaten by Carr’s dog Potchky. He had to retype the ending from memory. These facts are all contested. To one degree or another. Well, the details of Kerouac’s epic typing spurt have changed with each re-telling, including Jack’s. And the manuscript he wrote is long gone. Sure, the thing itself is still in the world, bought in 2002 for a little more than two million dollars by the man who owns the Indianapolis Colts, and it is currently traveling the U.S. in a road trip that started in 2004 and has already made stops in San Francisco, Denver, and New York. I went to see Jack’s scroll last month at the New York Public Library. Sixty feet of it were laid out under Plexiglas in a long display case that had been aligned with a giant overhanging photograph of a stretch of two-lane blacktop. If you stood in the right place, you could see the reflection of the yellow highway strip falling down the length of yellow scroll, and there it was: Novel as narrative thread keeping the traffic in line.

Jack began defacing and erasing that manuscript – editing and emending, dropping and adding, second-thinking – almost as soon as the last foot of it rolled out of the typewriter, even before the dog got to it and Robert Giroux told Jack that no one at Harcourt Brace would be able to read a giant roll of papyrus. The scroll on display in the D. Samuel and Jeane H. Gottesman Exhibition Hall of the Main Branch of the New York Public Library was scored with pencil markings, presumably Jack’s; words were scrawled between the lines, paragraphs were blocked off for deletion, famous passages were cut, later to be restored by – whom? Kerouac? Or Malcolm Cowley, his editor at Viking Press, who published the book six years after Jack hit the carriage return one last time in the spring of 1951?

In any case, the scroll was published last fall for the first time, and its name, On the Road: The Original Scroll, raises the question of what anybody means by “original.” The Original Scroll reproduces Jack’s 1951 text without any of his later editing marks, though it includes some typos, if not his x-ing out of various lines and the many spots throughout the manuscript where Jack apparently thought twice, back-spaced, typed over his copy, and then moved on. His scroll is pock-marked with these type-overs, but The Original Scroll presents a clean copy. I guess it would be awkward or ugly or even irrelevant to reprint the thickly cancelled lines, but one of the pleasures of seeing Jack’s scroll is thinking about how much trouble he had with the left-hand margin. Clearly, the typing paper slid on its roller, floating slowly and evenly to the right on a declining slant. Jack let it slide until he couldn’t stand it anymore, and then stopped to re-align the page. His scroll doesn’t have neatly indented flush-left paragraphs, it has weird angled blocks marked by a left-hand margin that sneaks further and further off and then corrects itself, over and over. It’s not just a text, is a design scheme on architect’s paper.

On the Road: The Original Scroll does not reproduce that periodically slanting left-hand margin. It is On the Road unplugged, but not all the way. There is, for instance, a critical apparatus; unlike Jack’s scroll, it comes with four introductory essays, a dedication to the memories of Neal Cassady and Allen Ginsberg, and a quote from Walt Whitman. However, its editor, Howard Cunnell, has allowed a typo to stand in the opening sentence. “I first met met Neal not long after my father died. . .” That’s how both Jack’s scroll and The Original Scroll begin. The sentence uses Neal’s real name and meets him twice, and it ends with a dead dad and an ellipsis. In the version of On the Road that everyone knows, the one Malcolm Cowley published, the sentence goes like this: “I first met Dean not long after my wife and I split up.” The story of how Neal turned into Dean, and how a missing dad became a former wife, not to mention how a typo got cleaned up and how an ellipsis mark borrowed from Celine became a blunt, decisive full-stop, is the story of how Jack’s scroll of April 1951 was already – by the time he showed it to the first editor who refused to publish it – not the thing he typed in three weeks on stolen paper in a dead guy’s loft.

Hardly anyone but Allen Ginsberg read that scroll. Certainly not Robert Giroux. And Jack stopped showing it around after Giroux suggested that it would have to be more portable. Insulted, Jack never re-submitted the manuscript to Harcourt Brace, but he did start re-typing it. By the time Ginsberg pitched the book to Cowley in 1953, Jack had long since transferred the text of the scroll onto 8 ½ x 11-inch sheets of typing paper, making changes as he went. Nonetheless, he still couldn’t get it published. He waited five years before Cowley came through with an offer, and during that time, he kept messing with it. There were two more complete manuscript versions before its publication in 1957. There was a whole new book, Visions of Cody, which Jack insisted was the “real” On the Road, and which wasn’t published in full until he died. Visions of Cody is the angry draft you write after your editor takes you to dinner and asks you, in the most discouraging possible tone, “What is this book about?” You go home and say, “All right, I’ll start from scratch, but this time I’m not holding back on the gay sex and I’m going to get high with my reform school pals and tape-record all our conversations and then transcribe them word for word.”

Moreover, Kerouac had been taking notes for his road novel since 1947, and actively drafting it since 1949, when The Town and the City was published. For a while, he was writing something called Ray Smith, about “two guys hitch hiking to California in search of something they don’t really find.” Then there was The Hip Generation, focusing on a character named Red Moultrie and his half-brother Vern and their Denver clan of misfit men from the Old West. Even The Town and the City feels like a dry-run for On the Road. It starts as an evocation of Kerouac’s childhood in a French Canadian neighborhood in Lowell, Massachusetts in the 1920s and ‘30s, but then the war comes, and one of the characters moves to New York and meets Allen Ginsberg, and the rest is just kicks. Ginsberg is called “Leon Levinsky,” and that’s also his name in the first few pages of the scroll of On the Road, until Jack gives up the pretense and says, “I mean of course Allen Ginsberg.” By the time Kerouac finished drafting and re-drafting On the Road – after Ginsberg, and Cowley, and Jack’s agent, and the copy editor at Viking Press, and a team of nervous lawyers and libel experts all had a go at the book – Ginsberg was fictional, again. He was Carlo Marx and Neal was Dean Moriarty, and Jack was Salvatore Paradise, not a Quebecois Canadian whose first language was French, but an Italian American who spoke bop.

If On the Road seems instantaneous, it was also highly pre-meditated, and later wildly mediated. For years before he sat down to write the scroll, Jack had been rehearsing chunks of the book out loud for friends. It wasn’t a novel, it was just what he did at parties. He got drunk and said, “Lemme tell you about the greatest ride I ever got on the back of a flat-bed truck driven by a couple of corn-fed farmers from Minnesota.” Or, “Have you heard about how me and Neal and Luanne undressed in the front seat of Neal’s Hudson and she smeared us all with cold cream?” Jack had been dining out on those stories for a while, tweaking them, refining them. It was just an accident of technology and temperament that, when he sat down to record his act, he used a typewriter instead of a tape deck or film camera. The scroll version of On the Road is a dramatic monologue addressed, perhaps, to Joan Haverty, the wife whom, paradoxically, Kerouac was about to lose partly because all he ever did was take speed and write dramatic monologues.

Anyway, that’s what John Leland suggests in Why Kerouac Matters: The Lessons of On the Road (They’re Not What You Think). I should admit that Leland was once my boss at Details magazine, and it’s possible he fired me. Unlike Kerouac, I don’t remember everything. Leland is an astute critic and reporter for The New York Times, and a chronicler of the American avant-garde. His last book was Hip: The History, and it begins its story on a 17th century slave plantation and ends in trendy Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Why Kerouac Matters was published last fall by Viking Press to coincide with the release both of On the Road: The Original Scroll and a pristine hardcover 50th anniversary reprinting of the 1957 On the Road: A marketing package. I bought them all. Leland is one of the few male writers who has ever seemed interested in the women in Kerouac’s life, and he posits an interesting theory about how On the Road came by its tone of intimacy, immediacy, and urgency: It started as a letter Jack was writing to his wife, the wife he had just married and was just about to flee.

Leland quotes Joan Haverty’s memoir, Nobody’s Wife, which Haverty wrote intermittently for about a decade until her death in 1990, and which Joan’s and Jack’s novelist daughter Jan Kerouac published in 1995, about a year before her death. According to Haverty, she turned to Jack one day not long after they married, and said, “What did you and Neal really do?” And then Jack sat down at his typewriter and started writing. Don’t we all have that day, when we take stock of our significant ex-es for the edification, or safety, of our current love? That’s what Jack did. For three weeks. The scroll isn’t a novel, or even a memoir, it’s a letter to Joan – a kind of proto-blog that treats everyone who reads it like members of the gang under discussion. Neal doesn’t have a last name, not right away. You’re supposed to know it. We don’t see his face or hear much about his history. There’s nothing like those passages in Henry James where the young girl shows up on an English lawn and before she is even served her tea we get a ten-page flashback to her childhood in Albany. With Jack, it’s just, “Let me tell you about the dude.”

The scroll starts with Neal, and it ends with Joan. That seems to be Jack’s point. “Honey, I loved him once, but then you came along.” In the chunk of text that Potchky ate, at the very end of the scroll and the close of the non-stop narrative, Jack reaches Joan: “One night I was standing in a dark street in Manhattan and called up to the window of a loft where I thought my friends were having a party. But a pretty girl stuck her head out of the window.” Which is how Joan’s ex-boyfriend Bill lost his head, literally, sticking it out the window. Was that on Jack’s mind? Is there a more un-self-reflective major post-war American novelist than Jack Kerouac? “She stuck her head out the window and said, ‘Yes? Who is it?’ ‘Jack Kerouac,’ I said, and heard my name resound in the sad and empty street.’ ‘Come on up,’ she called, ‘I’m making hot chocolate.” Jack could never resist a sugar high – all that apple pie in On the Road – and he went up, and “that night I asked her to marry me and she accepted and agreed. Five days later we were married.” That’s not how it happens in the 1957 On the Road – instead of getting married, “we agreed to love each other madly.” In real life, he and Joan were married in less than two weeks and stayed that way for about nine months. And one night along the way, it occurred to Joan that she hadn’t really met her husband, and she started asking questions. “Honey, what’s up with your love for that hustler-bigamist-car thief-sex addict you talk so much about?”

“I first met Neal,” Jack starts, and 120 feet later he ends, “There she was, the girl with the pure and innocent dear eyes that I had always searched for and for so long.” For and for? I guess that’s poetic. It didn’t work for Joan, though. She never thought much of his writing. And while he was busy taking dictation from the Holy Spirit, she went off to her restaurant job and came home with one of the waiters.

I don’t know why anyone likes On the Road. It’s got no plot, just a series of events. There is no real characterization. For all its talk of landscape, it hardly shows how Iowa is different from Texas. What if Jack had gone to an MFA program? Imagine him sitting in a classroom at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop in 1951, chain smoking and wearing a fabulous shirt and trying hard to look like he doesn’t care as his classmates rip into another draft of his book. “I don’t see the story arc,” somebody says. Another guy is gentler. “Have you asked yourself, ‘What do my characters want?” “Drugs!” someone says, and they all laugh and now the gloves are off. “What have you got against women?” “I don’t believe you’ve ever really been to Mexico.” “You keep telling me how ‘gone’ everything is, but you don’t show it. How is Denver ‘gone?’” “Or Pennsylvania?” “Or Charlie Parker?” Then the teacher breaks in. He’s a married guy who’s secretly gay, and Jack has been flirting with him all semester, showing up in his office crushed and handsome and clutching a tattered copy of You Can’t Go Home Again. “He knows five adjectives,” the teacher says, fixing Jack with a meaningful look and counting on his fingers, “great and wild and vast and empty and sad.”

In my fantasy, Jack’s teacher is a stand-in for Paul Goodman, a member of the group of New York Jewish liberal intellectuals, a generation older than the beats, who cast a cold eye on Kerouac and his pals. Reviewing On the Road in 1958, Goodman says, “For even when you ask yourself what is expressed by this prose, by this buoyant writing about racing-across-the-continent, you find that it is the woeful emptiness of running away from even loneliness and vague discontent. The words ‘exciting,’ ‘crazy,’ ‘the greatest,’ do not refer to any object or feeling, but are a means by which the members of the ‘beat generation’ convince one another that they have been there at all. ‘I dig it’ doesn’t mean ‘I understand it,’ but, ‘I perceive that something exists out there.’”

Goodman is right, of course. The hypothetical workshop students are probably right. On the Road does everything wrong. Even after ten years of revision. Self-indulgent, repetitive, declamatory, it’s all sensibility: What it has to offer is the drama of a voice emerging. It’s all voice! Is it written as a letter, is it a story you tell at a party, is it a way of explaining to your wife why you will always love your buddies more than her? Is it just your stoned attempt to get down on paper everything that happened, in your own distinctive style, before your id intervenes and you find yourself writing a passing imitation of Thomas Wolfe? I would never recommend On the Road to writing students, not if they were already immersed in The Big Book of Flannery O’Connor’s Exquisite Craft.

And yet:

The damned thing works.

It has charisma, that’s all, like Julia Roberts, and you sit there feeling seduced by it and wishing it were better, all the while knowing that perfection would wreck it.

[…] The Charm of the Highway Strip […]